‘What I really find interesting is that we no longer know exactly what is going on in machine learning,’ emphasises Schröter. Explainable AI, i.e. AI that makes it possible to understand how it arrives at its results, is therefore also a major topic today. ‘AI can also produce nonsense, because it's just statistics,’ says the researcher. But disciplines such as particle physics have been working statistics for a long time. ‘You probably have fewer problems with AI there than in some other sciences,’ surmises Schröter. But that is precisely one of the questions being investigated in the project.

The special perspective of media studies

But why of all people is a media scientist working on this? ‘In its megalomaniac moments, media science assumes that there is nothing that is not mediated by the media,’ jokes Schröter. Animals are also intelligent, can use tools, recognise themselves in the mirror – and ants have a highly developed division of labour and even practice agriculture. ‘But no animal is capable of building libraries, which is why animals will never develop beyond their present organisational state.’ Civilisation functions by writing down knowledge and passing it on. This ultimately means that every civilisation depends on its media. In addition, media science sees humans as an effect that is produced by media order: ‘Humans are a system consisting of body, brain, speech and stored code such as address, bank details, etc.,’ explains the researcher. What we now see is simply a new medium that can be used to analyse large amounts of data and also generate new data.

For Schröter, it is clear that there is no such thing as an AI effect on research. ‘Research is far too variegated to allow such a generalisation,’ emphasises the 55-year-old. Of course, AI can make data-intensive research more efficient or even possible in the first place. Other areas, such as art history, often do not require such a tool. Still others, such as climate research, have been working with complex computer simulations for a long time in order to tap into the complexity of their specialised field. Schröter can imagine that AI will be slow to find its way into this field, as well-functioning methods already exist.

Looking over the shoulder of AI users

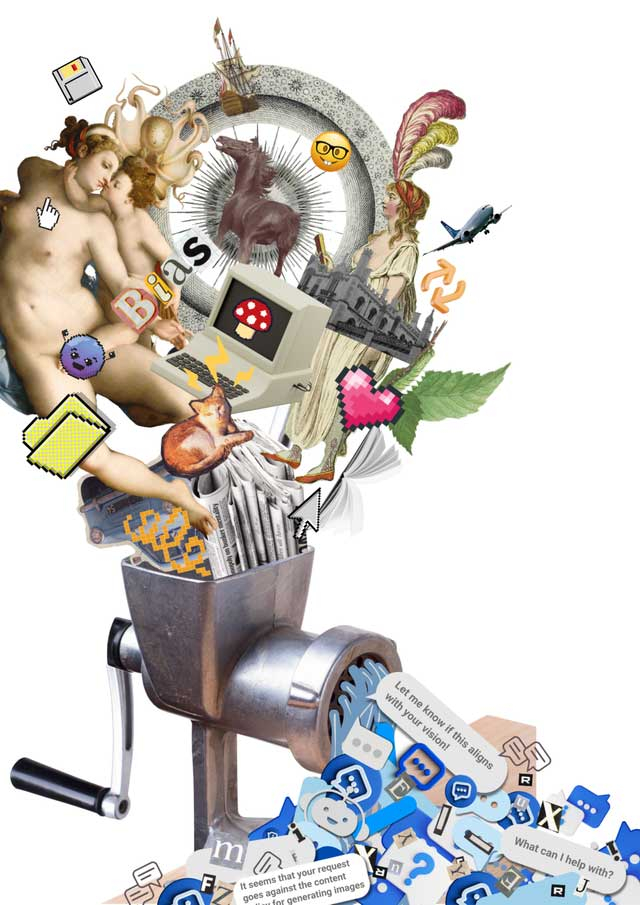

The project team is approaching these questions from three directions. Firstly, the researchers are looking at AI from a scientific-historical perspective: ‘Data is not simply a given, but has to be measured and collected,’ explains Schröter. ‘Our focus lies on the people who don't appear in the data, how data sets are biased or where there are copyright infringements.’ Why is data the way it is and what are the consequences?